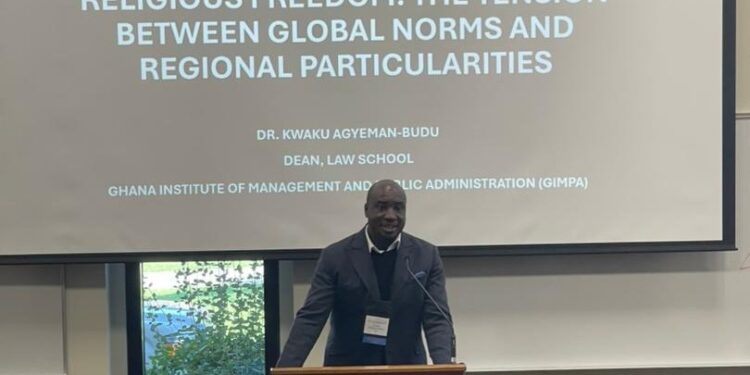

Dean of the GIMPA Law School, Dr. Kwaku Agyeman-Budu, has delivered a lecture at the 2025 Law and Religious Conference held at the Brigham Young University (BYU) in Provo, Utah, USA, from 5th to 8th October on the theme, “Cultural Relativism and Universality in Protecting Religious Freedoms: The Tension between Global Norms and Regional Particularities.”

Dr. Agyeman-Budu was invited by BYU’s Center on Law and Religion Studies to the Annual Conference in recognition of his knowledge and expertise in International Law, in particular International Human Rights Law, International Criminal Law and Justice, and Global constitutionalism.

In his lecture, he emphasized that despite the guarantee of religious freedom as a basic human right, protecting belief and conscience for all people by numerous International Human rights instruments,

There was still a challenge in the real-world application of this universal guarantee in that, “despite these legal guarantees, religious liberty faces obstacles due to cultural, political, and social diversity across nations and true religious freedom remains difficult to achieve globally, with unresolved challenges impacting human dignity and equality.”

Dr Agyeman-Budu subsequently turned his attention to legal issues and precedents in Ghana and other countries to bring perspectives on the topic. He talked about the Ga Traditional Council’s enforcement of the ban on drumming and noise-making for the Homowo festival and how the same is supported by Article 11 (1) of the 1992 constitution, which recognizes customary law as part of the laws of Ghana, and the fact that religious freedom is also guaranteed by the Constitution of Ghana as well, often resulting in conflicts between two constitutional rights.

He also discussed Ghanaian cases such as “Tyrone Marhguy v. Achimota School & Attorney-General (High Court 2021). The case centered on whether Achimota School’s policy requiring male students to keep their hair “low, simple, and natural” infringed upon Tyrone Marhguy’s constitutional rights.”

“Marhguy, a Rastafarian, maintained that his dreadlocks were an essential expression of his religious beliefs, and the school’s refusal to admit him unless he cut his hair violated his rights to education, dignity, and freedom of religion.

“The court held that the refusal to admit the applicant because of his dreadlocks, which is a manifestation of his religious right, is a violation of his human rights, right to education, and dignity.”

The next case he looked at was “James Kwabena Bomfeh Jnr. v. Attorney-General (National Cathedral & Hajj Board case).

In this case, the ‘Plaintiff sought a declaration that government support for religious initiatives—specifically the National Cathedral project and the Hajj Board—violated the 1992 Constitution’s guarantees of equality and religious freedom, and that Ghana’s secular character barred such state involvement.

“The suit asked the Court to hold that allocating public land/facilitating religious projects amounted to unconstitutional endorsement/entanglement with religion.

“The Supreme Court dismissed the action. It held that Ghana’s constitutional order, while guaranteeing freedom of religion and equality, does not impose a rigid “wall of separation.”

“Rather, Ghana’s brand of secularism permits recognition and reasonable accommodation of ‘religion by the state (e.g., administrative facilitation for the Hajj; steps toward a National Cathedral), absent clear constitutional breaches.

Dr Agyeman-Budu concluded his lecture by arguing that “the protection of religious freedom in a pluralistic world requires a sophisticated approach that rejects simplistic choices between universality and relativism.

“The universalist project is weakened if it ignores the legitimate diversity of human experience, while cultural relativism becomes a dangerous doctrine if it allows states to abrogate fundamental freedoms under the guise of tradition.

“The framework of ‘contextual universality’ offers a viable path forward. By firmly defending a non-negotiable core of religious liberty while embracing a flexible, dialogue-oriented approach to its implementation, we can ensure that the right remains both normatively robust and practically effective.”