Michelle Obama’s new book, “The Look,” is many things. It is an Amazon bestseller. It is a glossy photo book full of fashion. It is the story of the expectations that were heaped upon the first Black First Lady. And it is the third installment of a trilogy of books by Mrs. Obama that focus on self-realization, including her memoir, her advice book on overcoming adversity, and, this time, a meditation on the power of clothes.

But most of all, it is a historical document, capturing a pivotal moment in the evolution of the role of first lady when clothing became an even bigger part of communication. When, in other words, dress became an officially recognized part of the job. That’s a bigger deal than it might appear.

Mrs. Obama was, after all, the first lady to have a stylist — or “valet,” as Meredith Koop was called — on the East Wing payroll, one employed to help define the visual strategy of the first lady for every occasion, from public hula hooping to significant pageantry moments.

Before the Obamas entered the White House, first ladies like Jacqueline Kennedy, Nancy Reagan, and Hillary Clinton may have worked with a designer on their dresses for inaugural balls or state dinners, but the relationship was more one of grace and favor than a formal structure.

It was more about pageantry and propriety than diplomacy, and the first ladies tended to choose one designer (Oleg Cassini, James Galanos, Oscar de la Renta) and stick with him.

After Mrs. Obama, however, Melania Trump and Jill Biden each employed a stylist — Hervé Pierre for Mrs. Trump and Bailey Moon for Dr. Biden — who served as a liaison between fashion brands and the East Wing.

They collaborated with numerous designers for various occasions, often with a specific set of political priorities in mind. A new template had been created, and it became the norm.

Why that happened is, in large part, the subtext of “The Look,” which was released by Crown last week, and it is why the book matters. It lays bare, in an unprecedented (and easy-to-read) way, how a wardrobe was transformed into a vehicle of soft political power

As the first Black First Lady, Mrs. Obama knew that her every move would be scrutinized, including every outfit. She had to represent all sides of a fractious country, and she had to do it as the first first lady of the social media age.

The ability of the world to see and track her every appearance was far greater than it had ever been, and the ability of the world to comment on her every appearance was also greater.

Her image — the pictures making their way around Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook — mattered in a way it never had before, and thus the choices involved with creating that image mattered. The stakes had changed when it came to clothes.

As Mrs. Obama admits in the book. There had been speculation about the purpose behind many of her fashion choices as first lady in several books, including “Everyday Icon” by Kate Betts and “Michelle Obama: First Lady of Fashion and Style” by Susan Swimmer (not to mention in numerous articles by critics like me).

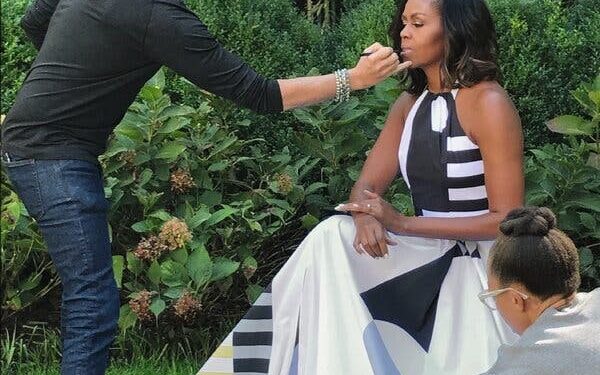

But this is the first time she has overtly addressed the subject of her style and credited the team — Ms. Koop, the stylist; the hairdressers Yene Damtew, Njeri Radway, and Johnny Wright; the makeup artist Carl Ray — that helped make it happen.

Thus, she writes, the decision to choose Jason Wu, then a young, relatively unknown Taiwanese-born New York designer, to design her inaugural gown was about demonstrating “that I was going to champion people and voices and talents that were too often overlooked.”

Those who, she went on, “represented the diverse talent of American fashion design that I wanted to showcase to the world.”

Thus, the approximately 100 different looks from Mrs. Obama’s time as First Lady are memorialized in “The Look,” excluding what she wore during the campaigns or after the Obamas left the White House. That’s a lot of clothing for one woman to wear, or shop for, in only eight years.

Especially when the criteria for each look being chosen also included diplomatic outreach, as when Mrs. Obama turned to a designer whose background bridged the United States and one of its allies for a state dinner or visit — all the better to, as she writes, “pay respect.”

Especially when there were also practical concerns to take into consideration — not just the mores of different countries, but the fact that Mrs. Obama’s clothes couldn’t restrict her movement, had to allow her to hug someone if desired, and had to be invulnerable to makeup that might rub off during contact.

Though Mrs. Obama writes about all of that in “The Look,” as well as the often-racist criticism she received for wearing sleeveless dresses, one subject she avoids is cost.

She does note that she tried to introduce “affordable but fashionable brands into my closet,” including J. Crew. Still, there’s no avoiding the fact that acquiring this many outfits is an enormous expense — a burden borne by the first family, not the state.

One way this cost is managed is for a designer to “gift” an outfit for a major public event to the country. This means that while the first lady may wear a gown once or twice, it is placed in the national archive or a presidential library rather than her closet.

Still, that doesn’t change the takeaway of “The Look.” The extent to which Mrs. Obama adapted her own style to the one she believed the country needed became apparent once she left the White House, as evidenced by her subsequent book tours and related fashion experiments. A Canadian tuxedo! Thigh-high Balenciaga boots! Straight from the runway, Chanel!

And that further underscores the point of this book: For any first lady, selecting the (many) garments that will define her tenure is not something that happens by accident. Nor should it be: It’s work.