President Trump has an unconcealed hunger for natural resources from abroad and the power they could grant him. He declared that the United States intervened in Venezuela to “take the oil,” betting that investors would put up at least $100 billion to revive a decrepit industry.

His gamble is that countries will still want to buy oil from America to power their cars, trucks, ships, and planes for decades to come.

Though China is the world’s largest oil importer, its leader, Xi Jinping, is less brash about coveting foreign resources. The country’s leadership is pushing hard to replace oil with electricity.

Chinese technology companies are paving the way for a world powered by electric motors rather than gas-guzzling engines. It is a decisively 21st-century approach not just to solve its own energy problems, but also to sell batteries and other electric products to everyone else.

Canada is its newest buyer of EVs; in a rebuke of Mr. Trump, its prime minister, Mark Carney, lowered tariffs on the cars as part of a new trade deal.

Though Americans have been slow to embrace electric vehicles, Chinese households have learned to love them. In 2025, 54 percent of new cars sold in China were either battery-powered or plug-in hybrids.

That is a big reason that the country’s oil consumption is on track to peak in 2027, according to forecasts from the International Energy Agency.

And Chinese E.V. makers are setting records — whether it’s BYD’s sales (besting Tesla by battery-powered vehicles sold for the first time last year) or Xiaomi’s speed (its cars are setting records at major racetracks like Nürburgring in Germany).

These vehicles are powered not by oil but by domestically generated electricity from coal, nuclear, hydropower, solar, and wind.

In 2000, China produced only one-third as much electrical power as the United States; by 2024, it produced nearly two and a half times the U.S. level.

China’s surging energy investments went primarily into building new coal-fired plants, which the country has in abundance. But over the past decade, it has also moved quickly to build cleaner energy sources, especially wind and solar.

China now generates more electricity each year than the United States and the European Union combined. It has close to 40 new nuclear power reactors under construction, compared with zero in America.

Last year, Beijing announced work on a new hydropower dam in Tibet that will have triple the capacity of China’s Three Gorges Dam, currently the world’s largest power station.

China isn’t just building gigantic amounts of power; its businesses are reshaping technological foundations to electrify the world.

China spent decades trying to build world-leading automotive champions; the results were not impressive until EVs arrived. Their adoption allowed Chinese automakers to stop trying to beat the Germans at building better combustion engines and instead leverage their greater expertise in electronics.

If an EV is a smartphone with tires, then it makes sense that the country that makes most of the world’s electronics would also make nearly half of its cars.

Several technologies had to mature before they could be electrified. The lithium-ion battery was invented by American and Japanese scientists before Chinese companies took over most of this industry in the 2010s.

The United States also used to dominate the production of rare-earth magnets, the crucial component in electric motors; China now makes more than 90 percent of these magnets.

The oil-burning products that can now instead be powered by batteries and electric motors include not only cars, but also bikes, buses, and even some boats. Heavy industry and building temperature control are also being electrified.

And a future in which many noisy, gas-powered household tools can be electrically powered is in reach: Even the foul and loud lawn mower and leaf blower are gradually being replaced by a more gentle thrum.

Some products may never be electrified. Battery packs will probably not power a long-haul flight or container ship (though cleaner fuels are possible). But the opportunity to electrify almost everything else will grow over the next decade, and China is leading the charge.

The southern city of Shenzhen, which has been producing Apple products for two decades, is leveraging its expertise in electronics — as well as more advanced batteries, magnets, and chips — to remake whole categories of transportation, household, and industrial products in the image of the smartphone.

As the world moves away from combustion engines and toward batteries, it will look away from oil producers and toward factories in Shenzhen.

The United States is far behind this competition. On the one hand, Elon Musk has done more than anyone else to raise the status of electric vehicles and to drive technological improvements associated with them.

But the broader U.S. industrial base has mostly shed its capabilities in batteries and rare-earth magnets, in part out of a deliberate effort to move these factories to China. American companies building drones or other products of the new electric age are also far behind their Chinese competitors.

Electrification demands engagement with the messy world of building power plants and manufacturing at scale, which are China’s strengths. But Silicon Valley has instead preferred to work in the realm of highly profitable digital businesses.

Technologists like Sam D’Amico (who is making a high-powered electric-induction stove) and Ryan McEntush (a venture capital investor) have lately sounded the alarm at how comprehensively ahead Chinese capabilities have become.

The United States could compete by building better drones and electric vehicles if its businesses had greater access to electricity and a vital industrial base.

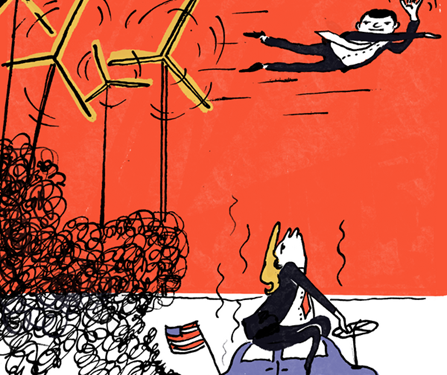

But it is governed by a president who is enthusiastic about powering the future with fossil fuels and has a personal pique against wind turbines, calling them the “SCAM OF THE CENTURY!” His administration is slow-walking approval of and cancelling new solar and wind projects while favouring coal and gas, which makes it more difficult to electrify.

No product is more important to electrification than batteries, yet an infamous ICE raid targeted a Korean company constructing a battery factory in Georgia. Meanwhile, Mr. Trump’s tariffs have hamstrung American manufacturing, which has lost around 70,000 jobs since April.

America had better shape up before losing out to an electric age ushered in by Beijing. Otherwise, it will be stuck with outmoded products at home while China conquers markets through better technology.